1. Moakley said earlier that Coins is associated with the Wheel because the Wheel is round and probably also because prudence is needed to manage money.. It seems to me that prudence is needed everywhere in life, even love. And there are also round objects in the Moon and Sun cards, which she associates with the Triumph of Time. Time was explicitly associated with Prudence in medieval and Renaissance times. The virtue is often shown looking forward, back, and to the side, signifying future, past, and present, both before and after the time of the PMB. Herr observation that the Queen of Coins (I would add: also the Page and perhaps the King) has the same design of dress as the Fortune lady does give one pause for thought. The same is true in the earlier Brera-Brambilla deck (although not for the Page and Knight). However there the same design is also on the Baton court figures. Unfortunately we do not have the Wheel card for the Cary-Yale. It may well be that in the PMB, the suit of Coins was indeed associated with the Wheel of Fortune. I see no reason to think that it was true during the time of the previous duke.

Putting Coins later, for example before the Devil (money as the root of all evil?), would make for a more even spacing of the suits. A better solution, in my view, would be to make the correlation of Coins with Prudence something that would have been done in the CY and then gradually gotten lost. Assuming the absence of the Devil and Tower (at least from the CY, if not from the PMB), and with only one Celestial (the Sun for Time, as the round object, or perhaps no round object at all, if the Celestials were absent from the CY or a predecessor, not necessarily in Milan, and Time was represented by the Old Man, an even spacing would work more easily.

2. I discussed the Chi=Gold equation in relation to Staves, where the crossed legs also appear. It has more relevance to Coins than to Staves, but whether the X sign was ever actually used to represent gold I do not know.

3. A "faience" is, per Google, "glazed ceramic ware, in particular decorated tin-glazed earthenware of the type that includes delftware and maiolica." It is named afterf Faenza, famous for such products and still producing them. Also, the Piero di Cosimo referred to is a 16th century painter, not one of the 15th century Medici.

4. The Gobbio (Hunchback) was also known as the Vecchio (Old Man) but only seldom Time, despite his hourglass. The change to a lantern probably occurred before most of the lists were drawn up. Even in the Metropolitan Sheet that Moakley looked at, he carries a lantern.

5. In minchiate, the elements and signs of the zodiac are at some remove from the Hunchback. They go between Charity, number 19, and the unnumbered Star card, while the Hunchback is at 11. But since the zodiac signs roughly correspond to the months, they could legitimately be associated with Time. Both they and the Sun and Moon as well. Moakley thinks the latter two are better associated in the minchiate with the Triumph of Eternity, as the "captives" of Eternity. But that would also apply to the zodiac signs, it seems to me. For the minchiate, it will be recalled, she associates the four virtue cards of Hope, Prudence, Faith, and Charity with Fame, apparently in its meaning as "Glory". That would also seem to be the meaning in minchiate, where the Judgment card is called "Fama". That of course is not Petrarch's meaning, but in Italian "Fama" applies to both. It is the interpretation that applies to people without earthly fame.

6. It seems significant to me that Muzio was guilty of "XII treasons". It corresponds to Judas as the 12th disciple, and of course the 12th triumph, in every 15th-16th century case. Also, since it is the father of Francesco Sforza, supposed co-commissioner of the deck, it is not necessarily a negative card. His green leggings suggest germination (like the green sleeves), and there is a hole in the ground under his head, as though he is being planted. Muzio's action upset the balance of power that was preventing a resolution of the schism. He deserted (not exactly a betrayal, as his loyalty was limited) an anti-pope. And he germinated the greatest condottiere in Italy.

7. If debtors were hung upside down, that raises the question of whether the man on the card, in Florence and Bologna, is not perhaps merely a debtor and not Judas. after all, one deterrent to debt is the shame incurred. However debtors in 15th century Italy do not appear to have been depicted hanged by their feet. That was only for people guilty of infamy, which were mostly traitors. The only exception might have been if he were a Jew, thought, for example, to have fled the city taking his creditors' money with him. The Catelin Geoffroy Hanged Man likely is a Jew, because of the type of depiction. But that is not Florence or Northern Italy. I don't think the Charles VI Hanged Man is supposed to represent a Jew in Florence. I discussed this at viewtopic.php?f=12&t=971&hilit=debtors&start=50#p14472.

8. Her account of flying devils is relevant: they and the angels fight for souls after death in the air. That may indeed be why Temperance in the French decks, where it is 14, has wings. The Devils on the card always have wings. Piscina in c. 1565 saw the "demoni" as representing the sphere of air (http://www.tarotpedia.com/wiki/Piscina_Discorso_5).

9. In Tarot, Jeu, Magie (p. 36) Depaulis advanced the theory that "Maison-Dieu" came from "Maison de Feu", where "Feu" means the Devil. But he give no source. Moakley does so, albeit for the misspelling "maisondefie": a Katalog of Nuremberg, which her bibliography says is dated 1886. The title is from an eighteenth century deck, she says. Noblet, in whose deck we first know the term, was active in the 1660s, as Depaulis documents (p. 64). But maybe "maisondefie" goes back earlier, with the more correct spelling, in France, of "Maison de Feu", which transforms, misreading imprecise woodcuts, to "Maison-Dieu".

Even if this is right, there is the question of why it would do so and be accepted. I see in Robert's Dictionnaire Francaise that one meaning of "maison-dieu" is given as "Temple of Jerusalem", which famously was destroyed twice, not by God, but no doubt was interpreted as such, by Christians and also Jews who saw their people straying from God.

In the Oxford English Dictionary, the term has a long history as meaning a poorhouse for the indigent, or a place where people went to die (or recover). Either way, they would have time to be penitent and to ready their souls for God. The meaning a place for the deadly ill fits with an image in the so-called "Schoen Horoscope", in which the astrological houses are given illustrations fitting the house but reminiscent of tarot cards (https://2.bp.blogspot.com/_Lu-6PwakMv0/ ... vSchon.JPG, image on right). In that sense the penitence might continue after death; in the painting done to commemorate Dante in Florence's Duomo, 1465, Purgatory looks much like the Tower, with a ring of fire on top (https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjeMd5LPNkH8QpfgiyQgJsyyHCU1ahEvWw12eEwnF2ifcFIPpmEcJ6GbJhaJQ-8-wqsrR1nCMY_ZqPrgleu-xX1Iqz19TqzfRlTZp2tAcLBairdG0Jkkx8r0CC9Lfq5TFanIUzOlt9ar0I/s400/17aDANTE_1200-900.jpg).

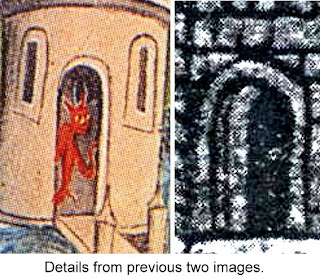

7. I didn't know the "Mantegna" painting (http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-LGp8GI_Hprk/T ... _limbo.jpg). Actually, according to the internet, it is by Giovanni Bellini, 1475, and called "descent into limbo", but it is very faithful to the Mantegna engraving "Descent into Hell", 1469, it is based on. (However the "Anonymous Tarot de Paris" bears some similarity.) It is true that in the early decks we don't see people falling off the tower, but that painting does not seem to be the inspiration when we do. There is no cliff or hellmouth in those cards, unless you count the door to the tower itself, which does not seem quite appropriate. The Metropolitan version she uses (since there is none in the PMB) does have a devil in the doorway, although it isn't easy to spot. The devil is more obvious in another c. 1500 image, "Nimrod's Tower" in Lydgate's Fall of Princes, done some time after the text was done, which was around 1450, perhaps as late as the earl 16th century (as I read in the introduction to this or another of Lydgate's works). I found a good color image, but somehow it is reversed (http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-CPi-nQqQhf8/U ... cesDet.jpg). It is strikingly like the Tarot de Marseille version with the falling figure (plus one lying on the ground) first seen in the 1660s. Here are the relevant details of the card and the illumination (I take it from another post of mine)

As far as the source of the Tarot de Marseille image (and perhaps of the Lydgate), the image of human looking figures falling from a crumbling tower was common enough in church settings, at least in France. They described the "fall of the idols" as the Holy Family flees into Egypt. Jean-Michel David explains this with excellent images: http://newsletter.tarotstudies.org/2014 ... -numinous/. All that is missing is the devil in the doorway to these pagan temples.

I suppose that Death and the Devil would have been appropriate in ribald contexts such as Carnival, even if the examples are later.. However the images were common enough otherwise. An old man on crutches might have been a subject for mockery by some, but even then it would have been in poor taste in a public festival. The men on crutches in "Battle between Carnival and Lent" mostly evoke our pity. In Milan it would have been in especially bad taste, because Filippo Maria was on crutches and the Sforza were emphasizing continuity with the Visconti. The PMB Hanged man does not look like an object of mirth, especially for the Sforza, where Francesco's father had been subject to that depiction. The Charles VI image is indeed a bit comic, as the moneybags he clings to simply tighten the ropes and add to his pain. Chasing Judas into Hell would no doubt be amusing, but I'm not sure seeing him hang would be A burning tower or a Hellmouth would also be entertaining, but for it to be ribald there would have to be a really bad person going in, of which there isn't.

No comments:

Post a Comment