This is certainly not an order we are used to, even without the insertion of the suits at various points. . It comes from the Tarocchi Appropriati published by Bertoni, dated, according to Dummett (Game of Tarot, p. 391, "between 1520 and 1550, more probably nearer the later date", and of Ferrara. This is at least 70 years after the PMB and from a different part of Italy. We now know, thanks to Michael Dummett's intricate study of numerous orders of triumphs in different sources at different times, that the orders divide into three basic types:

- type A, that of Florence and Bologna, which have the virtues all in a row after the Pope, and the last two cards go Mondo-Angelo;

- type B, that of Ferrara and Venice, which has as its last three cards Angelo-Justice-Mondo; and

- type C, of Milan and France, which has Justice as 8, Fortitude as 9 or 11, Temperance immediately after Death, and the last two cards as Angelo-Mondo.

The third example (after the Bertoni poem and the Steele sermon) is a set of uncut cards with numbers on them that is preserved in the Metropolitan Museum, New York. The order there is the same as in Bertoni, except that the Popess is lower down, third instead of fourth. She sees the position of the Popess as descending over time, ending up in second position

In both the A and C orders, in fact, the Popess is in 2nd position. Given that we don't know which of the three types orders is the earliest, all we know, regarding the Popess, is that she is one of the four cards from II to V, of which V is the Pope and the other two are the Empress and Emperor.

We now have a fairly good idea that between the "Steele Sermon" and Bertoni, the "Steele Sermon" is probably earlier, because the watermarks on the paper are from around 1500, and the sermons in it are likely from before then. This is important because the "Steele Sermon" order, as she failed to notice, is not the same as that of Bertoni, in one important part of the sequence: namely, in the “Steele Sermon” Temperance is VI, Love VII, Chariot VIII, and Fortitude IX (http://www.tarotpedia.com/wiki/Sermones ... _Cum_Aliis). Had she adopted this order—which is surely the earliest of the three she considers—her argument for trumps II-V as “captives of love” would have been stronger, since Love is closer to them (although Temperance still has to be dealt with), and also her argument for the influence of Petrarch, since Petrarch has Love before Chastity (=Chariot).

The A and C orders, if either of them applied to the PMB, also make Love closer to cards II-IV.; in fact, they both put love at VI. This makes her case for II-IV as "captives of Love" even stronger. However her idea that Love and Chariot are in the middle between Temperance, with Cups, and Fortitude, with Batons, is not supported by either order. Moreover, her idea that Swords comes at the end is also not supported in either case, because its correlative triumph Justice is not at the end but around 8.

It is no wonder that her idea about suits being correlated with virtues has been ignored, and likewise her idea that Temperance and Fortitude are womb and phallus symbols (that part defended by me above, http://moakleyupdated.blogspot.com/2017/03/updating-chapter-3.html) on either side of Love, as charioteer, and Chariot, as vehicle. That placement only works (if at all) for the B order she has chosen. And while there is one prominent researcher who accepts the B order of the "Steele Sermon" as the original one (Andrea Vitali), he does not accept her "ribald" view of the sequence as it was originally (nor do I).

I, however, do think that the suits do correlate with the virtues, just not in the way she had it; and moreover, her "ribald" thesis is also true, just not in the way she had it. She can be fixed. However it one must also accept an order that is nothing like A, B, or C, yet has some justification in what has survived of the relevant documents. It applies to the Cary-Yale and uses the order and suit assignments for the trumps that are in fact presented on Yale's website (http://beinecke.library.yale.edu/collections/highlights/visconti-tarot, which the curator tells me is based on documents that "came with the cards" when Yale purchased them. I can well believe that they capture its original conception,

I, however, do think that the suits do correlate with the virtues, just not in the way she had it; and moreover, her "ribald" thesis is also true, just not in the way she had it. She can be fixed. However it one must also accept an order that is nothing like A, B, or C, yet has some justification in what has survived of the relevant documents. It applies to the Cary-Yale and uses the order and suit assignments for the trumps that are in fact presented on Yale's website (http://beinecke.library.yale.edu/collections/highlights/visconti-tarot, which the curator tells me is based on documents that "came with the cards" when Yale purchased them. I can well believe that they capture its original conception, At left. the titles in all-capitals are the cards preserved at Yale and the suit assignments and order given there. The titles in italics are my suggestions for missing cards. This is from Pratesi's note translated at http://pratesitranslations.blogspot.com/2016/02/jan-17-2016-ruminations-on-visconti-di.html. Franco was kind enough to include my explanation for this reconstruction in his note. That was in early 2016. I would two changes now. Instead of "Old Man" I would put "Time", not because I think that is the correct title for the card, but because I can't say, in my reconstruction, whether the card would have been the Old Man or the Sun. It is the Sun that has the same shape as the suit-sign for Coins. However the Old Man is what appears in the PMB. The first known Sun card is later. The other change is that I would make it clear that I am assert that these added cards (in italics) are in precisely the spots I have put them. It is for illustration only, assuming that the virtue cards are put next to each other even if in different suits. They are merely somewhere in that group of four cards.

In this list, it may seem odd that Justice would be associated with Love. However marriage in those days, and still is to some extent, was a contract, with mutual duties to be fulfilled: he, for respect and material support to his wife and family; her, obedience and respect, as well as faithfulness, along with bearing their children and managing the household. Even Filippo Maria Visconti, who reportedly never had sexual relations with his second wife, perhaps due to some superstition, still treated her with respect and provided for her well-being, as long as it didn't involve potential lovers. Fortitude, along with Faith and Hope, are what is needed when there is a bad turn of the Wheel. Temperance delays Death, governs Chastity (the meaning of the Chariot), and manages one's consumption so as to allow for Charity. Prudence traditionally governs Time, and in the highest sense, care for one's soul. I expect that other arrangements of the three missing virtues could also be justified. This one seems to me the best fit, but any specific order and resulting interconnections would have to be learned more or less by rote, from a teacher, because there are various possibilities and none is very obvious.

In relation to Moakley, only the order of the "knights in procession" (p. 41 of Ch. 4) and their associated virtues is different from my reconstruction. Justice and three other cards are still associated with Swords, Fortitude and three other cards are associated with Batons. Temperance and three other cards are associated with Cups. Prudence--or perhaps Plato's "Wisdom"--and three other cards are associated with Coins. No ribaldry is present in this 16 card sequence. That comes later in the tarot's development. Franco Pratesi has been good enough to quote my elaboration of this idea in his note "Elucubrazioni sui tarocchi Visconti di Modrone o Cary-Yale", translated by me at http://pratesitranslations.blogspot.com/2016/02/jan-17-2016-ruminations-on-visconti-di.html.

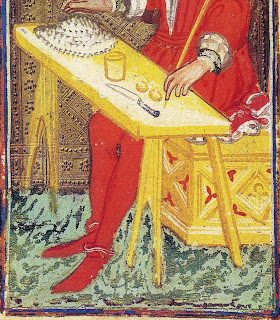

I turn now to the card Moakley calls "Bagatino".

Moakley calls the figure "Bagatino", asserting that the word has no meaning other than the card. Actually, it was the word for a coin of very small denomination in Bologna, according to the etymological dictionary. The heading of the section called "Bagatino" even gives a correct translation: quarter-penny, the smallest denomination of English money. It goes with his monicker "le petit", the little one. It fits the Carnival King, in the eyes of the Church, but also Jesus, God in the humble form of an itinerant beggar.

But in fact the earliest name on record for the card is in the "Steele Sermon": El Bagatella. Moakley says that this is a mixture of Spanish and Italian. Actually, I think "El" is an old Italian form of the definite article, too. It indicates that the card is not "La Bagatella", meaning "trifle", but rather the illusionist called with the same word, the "chatterbox" whose patter distracted from his hands. Ross found the word quoted by Muratori from a 13th century poem (translation by Marco Ponzi).

Fortune is an illusionist. So is the Bagatella. I don't what could be clearer. He is prestidigitator, someone fast with his hands, so as to create illusions. Absolutely no one since Moakley has seen him as a man sitting down to eat his pretended last meal. Well, I do, in a way, and I will get to that.Lassovi la fortuna fella /Travagliar qual Bagattella:

Quanto più si mostra bella, /Come anguilla squizza via.

I leave to you wicked fortune/ Who acts like a Bagattella:

whenever she seems most beautiful,/ she slips away like an eel,...

His presence in the deck gives the sequence a playfulness it does not have without it. At least that is so in the Tarot de Marseille version, with its dazzling young man, or the Ferrara version, in which children try to grab his accoutrements, or his presence in the "Children of the Planets" series done for Francesco Sforza in the early 1460s. Children are absolutely fascinated by illusionists; at least I was at a certain age. They would have a dog that did tricks, or a monkey, and maybe a confederate in the crowd who would cough up a frog (as in the Bosch workshop painting of c. 1500), while another confederate picked pockets. It is all very amusing.

But the PMB Bagatella is not very light, except for his bizarre hat. He looks thoughtful and weary.Not only that, he resembles images of Christ that the Bembo painted in Cremona. Compare him with Christ at the Ascension, done around the same time as the card:

Yet connection between an illusionist and Christ is, perhaps, Christ as logos, the one of whom it was said (http://www.latinvulgate.com/lv/verse.aspx?t=1&b=4):

Omnia per ipsum facta sunt et sine ipso factum est nihil quod factum est.

(All things were made by him: and without him was made nothing that was made.)

In that sense, the four objects of his trade--shells, wand, knife,

cups--do symbolize the four suits, the non-sacred parts of the game, and

the four elements, with the triumphs as the quintessence. These

associations were in fact made during the Renaissance, in various ways,

e.g. below, in connection with the four humors (except for the cup,

which is awkwardly given to the swordsman, even though water is

associated with the religious man):

In that sense Christ is a "Bagatella" in the 1298 sense (or Bagatello, as the Anonymous Discourse of 1570 calls him, with a similar explanation. I give the text, followed by Caldwell, Depaulis, and Ponzi's translation, with my comments on the translation in brackets:

Yet the scene on the card does suggest someone sad sitting down to a

meal, as a kind of secondary association. One might think of Jesus at

the Last Supper as well as the Carnival King. The sadness would be at

how the world treats the truth--there is such a long road ahead for his

followers. The straw hat, which Moakley takes as covering a dish with

food, also resembles the cover on the communion cup. Likewise, is

wand does resemble a scepter (as well as other things, such as an

innkeeper's nib pen), suggesting a king. Well, Jesus was considered King

of Kings (or "prince of princes", in Moakley's phrase).

Yet the scene on the card does suggest someone sad sitting down to a

meal, as a kind of secondary association. One might think of Jesus at

the Last Supper as well as the Carnival King. The sadness would be at

how the world treats the truth--there is such a long road ahead for his

followers. The straw hat, which Moakley takes as covering a dish with

food, also resembles the cover on the communion cup. Likewise, is

wand does resemble a scepter (as well as other things, such as an

innkeeper's nib pen), suggesting a king. Well, Jesus was considered King

of Kings (or "prince of princes", in Moakley's phrase).

Can there be an image that depicts both a thing and its opposite? The Fool is an example, in Moakley's eyes. Moakley puts him at the end of the procession, but he could just as well be at the beginning, where Anonymous finds him, next to the Bagatella. But the Bagatella is far more powerful. In the game, the is more powerful than any king, while the Fool has no power at all, except to take the place of a more powerful piece.

There is also the term "Juggler", which Moakley uses and takes as someone who keeps plates and cutlery in the air as an exercise in skill and humor. Actually, that is a modern sense of the term, unrecorded before the 19th century, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, 1997 Additions. The first date they find for its use is 1807. On the other hand, different meanings attach to the word in the years in question, more appropriate to an entertainer (sense 1, obsolete), trickster (sense 2, used mainly up to the 17th century), and conjurer (same). "Juggler" is an incorrect translation of "Bagatella" in relation to the English language currently. It is a good translation only in obsolete senses of the word. A better translation would be "street magician", for that is where he was found, in the piazzas. Mainly he was mounted on a platform, or bench, attracting crowds for the selling of patent medicines, looked down upon by the medical establishment (for that reason Dummett called him a "Mountebank"). He might also be doing the "shell game", luring in those who think their eyes are faster than his hands, who find at the end that they have lost their money.

In that sense Christ is a "Bagatella" in the 1298 sense (or Bagatello, as the Anonymous Discourse of 1570 calls him, with a similar explanation. I give the text, followed by Caldwell, Depaulis, and Ponzi's translation, with my comments on the translation in brackets:

Gli posa appresso il Bagatello, percioche si come coloro, che con prestezza di mano giacando, una cosa per un' altro parer ci fanno, il che oltre alla maraviglia porge vana dilettatione, non essendo il suo fine altro che inganno cosi il Mondo allettando altrui sotto imagine di bello, et dilettevole promettendo contentezza, al fine da guai, et in guisa di prestigiatore non havendo in se cosa premanente ne durabile, con finta apparenza di bene, conduce a miserabil fine.Well, yes, but so is the world itself, from which the road to the divine begins. Plato's Republic (of which Filippo's secretary had in 1440 completed a new, readable translation) compared the world of the senses to shadows cast on a cave wall from unseen puppets and an unseen fire. (To the followers of Augustine, buried at Pavia, Plato was the pagan whom Augustine had put in service to Christianity.) It is that world into which God descended to become Jesus, and which crucified him.

(He placed the Bagat [in Italian, Bagattello] next to him [meaning the Fool], because,like those that play with swift hands, making one thing look like another one, causing wonder and a vain amusement, since his only goal is deception, in the same way, the world attracts the others [literally, attracting others] with images of beauty and delight, promising happiness at the end of trouble, as a juggler it contains [literally, "in the manner of a slight of hand artist, having"] nothing either permanent nor durable, and [he?] leads to a miserable end, under the false appearance of good.)

Yet the scene on the card does suggest someone sad sitting down to a

meal, as a kind of secondary association. One might think of Jesus at

the Last Supper as well as the Carnival King. The sadness would be at

how the world treats the truth--there is such a long road ahead for his

followers. The straw hat, which Moakley takes as covering a dish with

food, also resembles the cover on the communion cup. Likewise, is

wand does resemble a scepter (as well as other things, such as an

innkeeper's nib pen), suggesting a king. Well, Jesus was considered King

of Kings (or "prince of princes", in Moakley's phrase).

Yet the scene on the card does suggest someone sad sitting down to a

meal, as a kind of secondary association. One might think of Jesus at

the Last Supper as well as the Carnival King. The sadness would be at

how the world treats the truth--there is such a long road ahead for his

followers. The straw hat, which Moakley takes as covering a dish with

food, also resembles the cover on the communion cup. Likewise, is

wand does resemble a scepter (as well as other things, such as an

innkeeper's nib pen), suggesting a king. Well, Jesus was considered King

of Kings (or "prince of princes", in Moakley's phrase).Can there be an image that depicts both a thing and its opposite? The Fool is an example, in Moakley's eyes. Moakley puts him at the end of the procession, but he could just as well be at the beginning, where Anonymous finds him, next to the Bagatella. But the Bagatella is far more powerful. In the game, the is more powerful than any king, while the Fool has no power at all, except to take the place of a more powerful piece.

There is also the term "Juggler", which Moakley uses and takes as someone who keeps plates and cutlery in the air as an exercise in skill and humor. Actually, that is a modern sense of the term, unrecorded before the 19th century, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, 1997 Additions. The first date they find for its use is 1807. On the other hand, different meanings attach to the word in the years in question, more appropriate to an entertainer (sense 1, obsolete), trickster (sense 2, used mainly up to the 17th century), and conjurer (same). "Juggler" is an incorrect translation of "Bagatella" in relation to the English language currently. It is a good translation only in obsolete senses of the word. A better translation would be "street magician", for that is where he was found, in the piazzas. Mainly he was mounted on a platform, or bench, attracting crowds for the selling of patent medicines, looked down upon by the medical establishment (for that reason Dummett called him a "Mountebank"). He might also be doing the "shell game", luring in those who think their eyes are faster than his hands, who find at the end that they have lost their money.

No comments:

Post a Comment